As the world celebrates the 50th anniversary of the first landing on the moon, the Boca Raton Museum of Art pays tribute to this milestone year by charting a different course that stands out from the rest, with the new exhibition Carol Prusa: Dark Light. On this journey, the artist invites viewers to honor the women astronomers who originally helped map the stars as she takes flight across the mysteries of deep space.

As the world celebrates the 50th anniversary of the first landing on the moon, the Boca Raton Museum of Art pays tribute to this milestone year by charting a different course that stands out from the rest, with the new exhibition Carol Prusa: Dark Light. On this journey, the artist invites viewers to honor the women astronomers who originally helped map the stars as she takes flight across the mysteries of deep space.

Her new exhibition is curated by Kathleen Goncharov, the Senior Curator of the Museum, and features never-before-seen works created specifically for this show – meticulous creations handmade by the artist using her signature silverpoint technique. The artist lives in Boca Raton and currently teaches painting as a Professor of Art at Florida Atlantic University.

“We sometimes get too distracted with the busyness and craziness of the trivial details in our daily lives. That is when we need artists like Carol Prusa to expand our horizons into the solar system, into the deeper unknown of dark space.” said Irvin Lippman, the Executive Director of the Boca Raton Museum of Art.

“As Carol explains, she has always been interested in science and cosmology. In the sixth grade she wondered about the Big Bang and ‘how it could be that there was nothing before there was something.’“

Carol Prusa, Quintessence, Silverpoint, graphite, acrylic on acrylic hemisphere with lens and internal video player/video, 2019

Prusa combines surprising materials such as sculpted resin, fiberglass, metal leaf, LED lights, black iron oxide, titanium, and powdered steel with the ancient craft of silverpoint, resulting in ethereal creations that command curiosity. Carol Prusa: Dark Light includes silverpoint, graphite and acrylic works on plexiglass and wood panels; light-speckled domes with internal lights and video.

“Carol Prusa is a visual alchemist whose work harnesses cosmic chaos and makes invisible forces materialize before our eyes,” writes Logan Royce Beitmen in the exhibition catalogue. “Drawing with actual silver and painting with powdered steel, Prusa’s use of materials defies expectations.”

Prusa’s new series of prints, created for this exhibition, honor the contributions made to science and astronomy by women who spearheaded early efforts to map the heavens. She was inspired by the life and accomplishments of Maria Mitchell, the first female astronomer in the U.S. who achieved international acclaim as the first American scientist to discover a comet.

Maria Mitchell Looking Through a Telescope, (detail) painting by Mrs. H. Dassel, circa 1851

Mitchell was a pioneering advocate for math and science education for girls and was the first female astronomy professor. At age 29, in 1847, Mitchell discovered the comet that would be named “Miss Mitchell’s Comet,” using a two-inch telescope. King Frederick VI of Denmark awarded her a gold medal, and she became the first woman elected to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Mitchell led an all-female expedition to Colorado in 1878 to observe the total eclipse of the sun. Her goal – bold for her time – was to encourage other women into her profession, at the dawn of America’s scientific age. Later astronomers honored Mitchell by naming a lunar crater on the moon “Mitchell Crater.”

Maria Mitchell poses with the first Astronomy class at Vassar College from www.vcencyclopedia.vassar.edu/

Following in Mitchell’s footsteps to witness solar eclipses, Carol Prusa was inspired by the life-changing effects she felt while witnessing these astronomical phenomena in Nebraska and Chile.

Prusa’s favorite quote by Mitchell captures the spirit of this exhibition: “We seize only a little bit of the curtain that hides the infinite from us.”

Carol Prusa, Totality, 2018, silverpoint, graphite, titanium white pigment with acrylic binder on 1/4″ acrylic circle. Courtesy of the Artist.

There were many women astronomers throughout history who led the charge in the field of astronomy, but with little recognition. Prusa’s new suite of prints challenges this lapse by honoring these women astronomers: Maria Mitchell, Henrietta Swan Leavitt, Annie Jump Cannon, Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, Vera Rubin, and Jocelyn Bell Burnell.

Maria Mitchell (seated) in her observatory at Vassar College, circa 1877. Photo from “Heroes of Progress: Stories of Successful Americans” by Eva March Tappan, 1921.

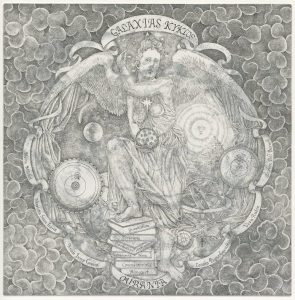

The portfolio of new prints by Prusa is called Galaxias Kyklos (the Greek term for the Milky Way), and the title page gloriously depicts Ourania, the muse of astronomy in Greek mythology.

Carol Prusa, Ourania, 2019, from Galaxias Kyklos (suite of prints in laser etched plexi box with letterpress colophon).

Other artworks in the exhibition are dedicated to women who served as human “computers” at the Harvard Observatory in the 19th century, painstakingly analyzing the many glass photographic plates from observatories around the world to map the stars.

The earnings of these women were substantially less than men in their field, and their labor too went unrecognized. Another woman scientist honored in this body of work is Rebecca Elson. She was a theoretical astrophysicist whose research focused on dark matter who died of lymphoma in 1999 at the young age of 39 and was also an accomplished poet.

“I am especially drawn to ideas and experiences that unsettle and coalesce in my art,” said Prusa. “Seeing a total eclipse for the first time, I was blown away by a euphoric feeling of floating, I was so moved that I literally fell backward.”

“When the shadow of the eclipse passed over, the world changed in a way I had never experienced before. The sun became a sharp black disc, Venus popped out and the sky to my right was night and to my left it was day. I was compelled to create this body of work to come to terms with this overwhelming feeling,” adds Prusa.

ABOUT THE AGE-OLD MAGIC OF SILVERPOINT

The age-old method has been used by artists, scribes and artisans since ancient times. The silverpoint stylus itself is a small stick of silver inserted into a wooden rod, similar to a pencil (except silver is used instead of lead). Silverpoint drawings are created by making a mark on a surface with this rod or wire made out of silver.

The photographer Bruce Weber has proclaimed that Carol Prusa is “one of the most innovative artists working in metalpoint today.”

Prusa has always been fascinated by science and cosmology, and learned silverpoint technique while teaching in Florence. Some of Prusa’s inspiration comes from the sciences of astrophysics, meteorology, and optics. She also incorporates Russian Orthodox and Tibetan Buddhist art-making traditions that she studied in the 1990s.

Just one of these works can take thousands of hours to create depending on the work’s complexity and size. The artist worked for countless hours on each individual artwork in this exhibition. Like her cosmic subject matter, her process of artmaking is extremely detailed, vast, and is considered awe-inspiring by her peers.

Prusa was nominated by Judy Pfaff and chosen by the American Academy of Arts and Letters as one of only 40 artists to exhibit in the 2015 Invitational Exhibition of Visual Arts, NYC (the selection committee that year was chaired by Eric Fischl).

“My practice becomes for me like a form of meditation that leads to bliss, like a Buddhist prayer,” said Carol Prusa. “The time-intensive process expands my introspection and reverie about our universe.”

Prusa’s work begins with her process of reading and research, but resolves with a tone of strange beauty encapsulating what it feels like to be alive.

Silverpoint itself is reminiscent of mercury, a liquid, and for Prusa, these works reflect the alchemical and transformational nature of art. She hopes viewers will pause and consider the abundance and fertility of life and how all things are interconnected.

Prusa studied embryology as part of her original training to become a medical illustrator, which she abandoned once she became an artist instead.

All of the works in this show have circular motifs, spheres that Prusa intended to spark a sense of infinity for the viewer. Although circles and spherical openings may imply feminine forms, Prusa has also created embryonic works that represent pure potential not limited to gender – like the pioneer women astronomers who transcended gender bias of their time to help create the maps of space that helped make the first landing on the moon a possibility for humanity.

Carol Prusa, (Detail) Nebula, 2019, Silverpoint, graphite, acrylic on acrylic dome with internal light. Courtesy of the artist.

“When I started to make this new series about eclipses, I drew upon my powerful memories of what it felt like to witness these astronomical wonders,” said Prusa. “An eclipse is dark light.”

Black, no matter how dark, still reflects light. I wanted to make black have depth and structure, and to be infinite. The eclipses influenced me in this respect, but this could also be a reflection on the times we live in. There isn’t dark without light ─ or light without dark.”